All of this changed in a month. With the streets empty of the usual traffic in April, supercars descended on midtown and East Drive, turning them into their personal racetrack. I often ended up feeling like I was watching Dom Toretto and Brian O’Conner racing in The Fast and the Furious. Of course, some burnouts were also thrown in.

Approximately 25% of all driving in America is work-related, while 27% is social/recreational (skewed towards the weekends). The rest comes from shopping, schools, errands, etc.

With most of the white-collar workforce transitioning to a work from home model and America putting a pause on heading out, driving overall fell drastically. This led to fewer fender-benders, accidents, etc., improving personal auto companies' financial results.

With loss-costs cratering, profits appearing egregious, and no end to the Covid-related shutdown in sight, many personal auto insurance companies offered cashback/rebates and discounts in the earlier months of the pandemic. However, there was a partial offset to the huge frequency benefits with emptier highways, roads, and streets resulted in higher severity of losses.

This arc continued into 2021, where it intersected with other factors adding to pressure loss severity. This included supply chain issues and high demand for new cars driving up the prices of used cars, which was not anticipated initially by the insurers. Also pressuring results was the slower improvement in employment, which drove up the cost of maintenance and repairs.

This slow uptick continued and then started impacting results over the past few months. Progressive’s July earnings saw the company miss its long-term 96% combined ratio target for the second month in a row.

As is often the case, there has been a renewed debate on whether personal auto carriers will be able to obtain the rate needed to counterbalance the recent worsening of loss-cost trends.

In response to these trends, companies have started taking steps to raise rates. This process requires approval from state regulators, which can take several months. After which, carriers can start increasing prices on the policies, a process which can also take several months to see the rate changes reflected in the losses, with most auto policies around six months.

This is a continuous process that personal auto carriers have undergone thousands and thousands of times. The fast-changing loss cost trends seen since the pandemic are raising fears that state regulators may not approve the rates needed by personal auto carriers to avoid margin compression.

However, the case for regulators objecting to or disapproving rate changes might have been overstated.

To put things in perspective, over the past 10 years, Progressive has only had disapproved (or withdrawn) 105 out of 2,617 rate filings. When regulators do disapprove a rate filing, it’s often because the carrier forgot to include a document or signature, rarely because they think the actuaries are wrong.

It is also common for regulators to request additional information before deciding whether to approve. Our analysis below looks at some of the feedback from Progressive’s recent rate filings and what it could mean for personal auto carriers as they pursue rate increases.

On the surface, it may appear that personal auto carriers are facing headwinds in pushing rate.

Moves on rate have been described as "excessive" and "overly reactive" by regulators.

This is not exactly what personal auto carriers hope to hear when they request to increase rates as a result of worsening loss cost trends.

Progressive has recently received push-back from regulators in Connecticut and Texas in response to its requested rate increases.

In Texas, a state which represents more than 10% of Progressive’s premiums, regulators objected to a request for a rate increase with an estimated overall impact of 4.7%, calling the selected loss trends “unrelated” to the supporting data. In Connecticut, which represents a smaller portion of Progressive’s book, at around 1% of premiums, a requested rate increase of 5.8% elicited many of the same objections as the Texas rate filings.

Instead of approving the rate increases, Texas regulators have gone as far as to suggest Progressive should provide further rebates to the policyholders, as it did during the pandemic.

Allstate has experienced similar regulatory pushback on its rate request in Texas of 6.7% in July, with state regulators indicating the selected loss trends are not supported by the historical trends the company provided.

But regulators’ disapprovals and objections are often business as usual.

State insurance regulators don’t have tracking devices in thousands of cars to gauge driving behavior, nor are they notified of accidents minutes after they occur. This leaves regulators with a somewhat lagging view of the marketplace while the rate requests take a forward view.

For Progressive’s rate request, Texas regulators pointed to the loss ratios in January – March 2021 being lower than the same period of 2019. We can understand why this would raise a red flag for regulators. The company’s results only made a notable turn in June, which would not have been evident to outsiders by the end of March.

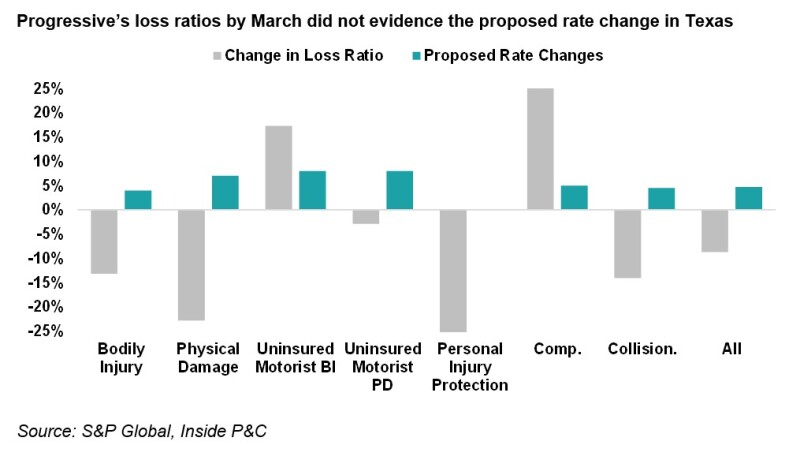

Below, we see in Texas, Progressive requesting rate increases where they predict the worsening of trends, although the loss ratios were not yet evidencing those trends.

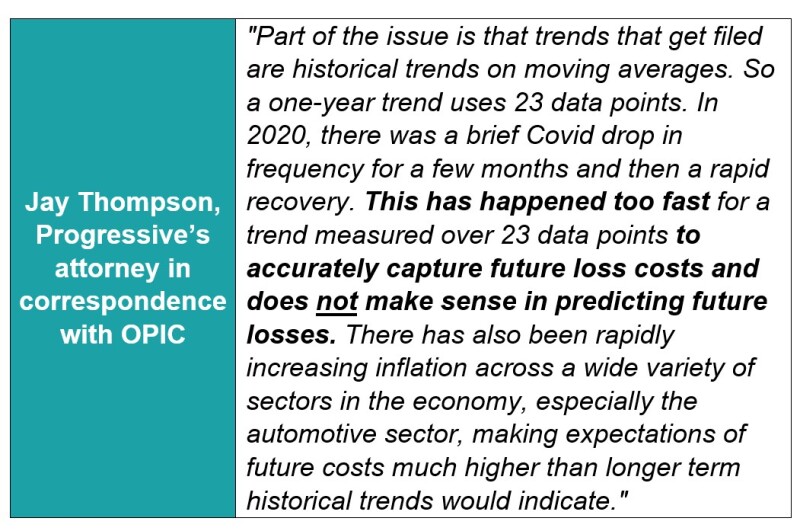

Progressive’s attorney summarized this well in his reply to state regulators:

This back and forth is understandable given the swiftness with which loss-cost trends have changed this year and personal auto carriers will likely be sharing more information on the loss-cost trends with regulators in order to get these filings approved.

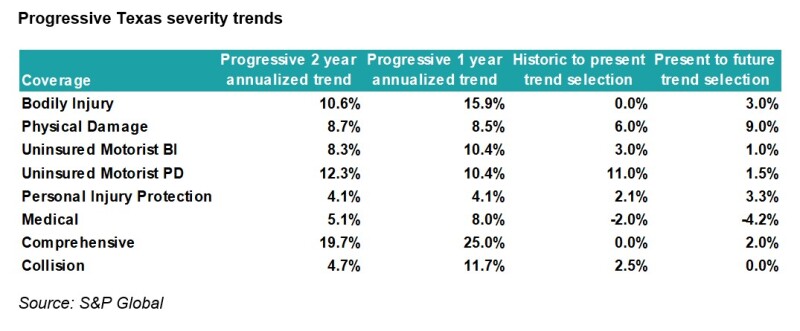

Filings show the extent to which frequency and severity are expected to rise.

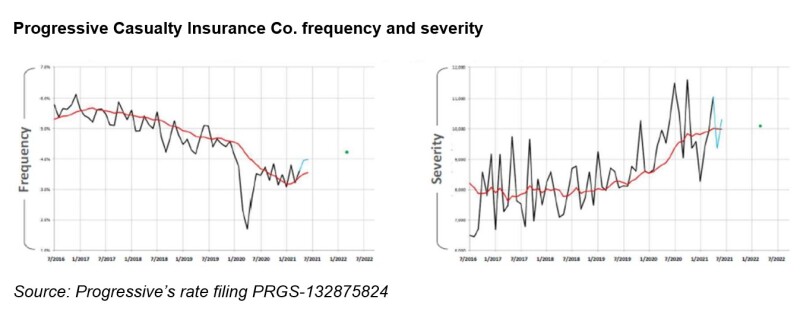

When drivers stayed home during the pandemic, the focus was on frequency benefits – less driving translating to fewer accidents. Looking at Progressive’s Texas filing below, we see frequency trends were down double digits last year as a result.

Fewer accidents meant fewer claims across the board, for both bodily injury and physical damage claims. The only area that didn’t see a benefit was comprehensive coverage. Comprehensive covers damage outside of accidents (like stolen vehicles), and went up slightly during the pandemic.

But as the economy re-opened, the trends reversed. As we see in the chart below, in its future trend selection, Progressive is assuming a full reversal and even suggests frequency will slightly worsen from pre-pandemic levels.

Severity, on the other hand, did not decrease during the pandemic. Instead, it has been rising and is expected to continue to rise.

A big part of the severity spike has been driven by the rise in used car prices. The spike in used car prices, along with worker shortages, has led to an increase in costs for coverages that require repair or replacement of the vehicle. These include physical damage, as well as comprehensive and collision coverages.

Companies have also pointed to more serious accidents since the pandemic. Instead of the low-impact fender-benders that would happen during rush hour traffic, drivers are getting into more serious accidents as they are driving at higher speeds.

Progressive’s Connecticut filing shows similar trends. In the graphs the company provided in the response to the regulators, we see frequency trends have reverted, and the company’s selection is slightly above levels seen before the pandemic lockdowns began. Severity trends have increased and are expected to stay elevated.

In summary, the worsening loss-cost trends are attracting more attention to the rate filing process. Still, personal auto carriers are jumping, and will continue to jump, through the necessary hoops to obtain rate approvals from regulators. Thus, we continue to view Progressive’s balancing act of pricing and loss-cost trends as part of a long term strategy, susceptible to the up and downs of the industry.