Businesses would do well to heed this advice as well. For example, McDonald's should have never offered pizza or spaghetti (for the record, the pizza was good, but that's a separate discussion). Likewise, BP and Exxon shouldn't have jumped into the mineral-mining business in the 1970s. Over-diversification, or diversification in the wrong direction, can distract companies from their core competencies and prevent them from doing what they do best.

Over time, when companies generate capital, sometimes this accumulation is faster than what can be deployed in their core business segments. With investors clamoring for such capital to be returned, management teams can feel like it is burning a hole in their pocket.

If one were to go back to the 70s, 80s, and 90s and trace the iteration of life and P&C firms stepping into each other's sectors, the overarching lesson would be that it's okay to sit on or return capital.

Life insurance companies historically were viewed as asset-gatherers playing on the mismatch of current and long-term interest rates. P&C companies thought of life as a means of float gathering, and perhaps a path to cross-selling. This ended up in a weird marriage of convenience, which seemed to work for a while. A high-interest-rate environment allowed the issues to be swept under the rug.

But then the life insurers started to get greedy. In the 1980s, with the proliferation of variable annuities, life insurers reduced the duration of their investment portfolios to benefit from high short-term interest rates. But as rates declined, the assets backing these liabilities did not generate enough earnings to exceed the premiums. As a result, life insurers chasing higher returns moved into real-estate and junk bonds due to higher crediting rates.

Unfortunately, this strategy ran into a wall in the late 90s due to a collapse in real-estate and junk bonds.

Real-estate prices pealed shortly before the 1990 recession and continued to drop throughout the next decade. In addition, a flash-crash of junk bonds in 1989 forced some savings and loan companies to declare bankruptcy and impacted the supply of bonds for the following year, causing investors (including life insurance firms) to lose a meaningful amount of their initial investment.

The one-two punch of real estate and junk bonds pushed some life insurance firms into bankruptcy. Notable failures included Executive Life, Mutual Benefit and Confederation Life.

This series of failures led to the "great unravel" where P&C and life insurance began to untangle from each other and go their separate ways, a trend which has continued in recent years.

However, recently we have seen examples of P&C firms such as Progressive and Lemonade looking at life insurance products again.

We do want to recognize that the new life offerings are mainly immaterial to the company's top and bottom lines and, in other cases, are a passthrough in terms of retaining risk. But history is a strict teacher, and it would make sense to take a step back and revisit how some of these issues played out.

First, once you're in a business, it is hard to get out.

Despite the hurdles, it would often take decades for P&C firms to ditch their life segments and find an interested buyer.

Allstate finally sold its life insurance business earlier this year, having discontinued annuity sales as long ago as 2014, and having seen life insurance sales peak in 2018.

The opposite has also been true, with life insurance companies selling off their P&C operations.

After Hurricane Andrew caused losses of more than $1.3bn to Prudential's P&C business in 1992, the P&C subsidiary's credit rating was downgraded by AM Best and placed on the watchlist by both Moody's and Standard & Poor's. But it would take nearly a decade for the company to sell.

The list below is by no means exhaustive, but it shows the death of a dream of cross-selling and a play on interest rates continuing to be high.

Secondly, divestitures aren't key to stock price success.

In our sell-side careers, P&C investors would often loathe to touch an enterprise with a life business. The sum of the parts (SOTP) analysis always made more sense for investment banking purposes. But savvy investors knew there weren't many examples of life and P&C enterprises trading at SOTP values.

So apart from the lack of a continued reason to dabble on both sides, companies faced sustained pressure and campaigns to break up or divest the businesses to return to a more pure-play franchise.

Although these divestments did result in simplifying businesses, it took much longer for the stock valuations to recover – although perhaps this was a sign of the levels of confidence in some of the management teams that made these moves. The chart below shows the stock performance of insurers since divesting vs. S&P peer insurance group.

Post-divestment, insurers recorded mixed results long term, suggesting the strategy is not so cut and dried.

Thirdly, Progressive's expansion example shows that life insurance’s impact will be immaterial to the top line.

In 2019, Progressive listed life as a potential area of growth (followed by electronic device insurance). The company pointed to unmet consumer needs in the segment, but we note that growth in the segment wouldn't benefit from its core advantage of sophisticated pricing.

Recall, the company's auto pricing model was initially years ahead of most competitors and allowed it to grow quickly while its competitors remained mired in inefficiency.

A 2004 report from InsurQuote and McKinsey showed that Progressive generated 131 different price points in quoting coverage compared to Nationwide's one price. This study showed the better pricing model that the company had created by gathering more information on drivers and building more indicative correlations between all the factors.

This advantage has been apparent in the company's results. Progressive has not posted an annual underwriting loss in two decades. However, what may be more impressive than the results it delivered is the firm's ability to simplify these concepts to investors. This effort has been rewarded by record-high multiples for a P&C insurer.

Progressive's expansion into commercial auto has proved successful so far, as the firm was able to apply the same pricing advantage in segmentation as it did in auto.

But Progressive's recent life launch steps into a different territory. To grow in the life sector, the company cannot rely on its proven pricing capabilities and must instead find an edge in its distribution and underwriting skills.

The company's property business growth echoed similar thoughts, with easy distribution and the advantages of bundling, but underwriting has not matched the same successes of the auto book.

Earlier this year, the company launched a term policy with Fidelity Life targeted at young adults looking to purchase a policy without a medical exam.

The chart below shows that, so far, the company has reported service revenues (commissions earned from third-party product sales) rising 20% year to date, but are a small proportion compared to the company's $40bn of net premiums earned.

Albeit on a much smaller scale, Lemonade has also had opportunities in selling life products to its customer base. After all, it makes sense for companies trying to app-ify P&C insurance to try to do the same for other lines.

But InsurTech is not about to change the game in life insurance.

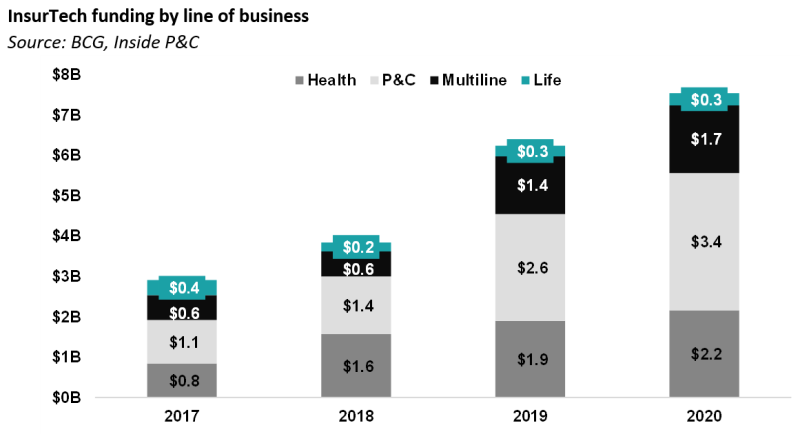

The chart below presents the breakdown of InsurTech funding by line of business. It shows that while InsurTech funding has increased significantly for P&C, health, and multi-line players, it has remained limited for life insurance. The lack of InsurTech attention and funding directed towards the business line reflects a consensus that life insurance might not hold as many opportunities for new entrants as other sectors.

The barriers to entry for a personal auto product are lower vs long-tail lines. You can get off the ground with numerous reinsurance partners, but life and annuity are a whole other ballgame.

In P&C insurance the gamble is on inflation and interest rates. In life insurance, the entire bet is on the direction of interest rates and how you manage around it.

Additionally, life and similar products are pretty long-tail in nature. This would result in founders being locked in for a longer duration and a commensurate valuation discount.

In summary, the industry may be coming full circle and returning to the decades-old promise of growth found in diversification. However, we anticipate that firms will only dip their toes into life instead of jumping in, and life insurance will remain a small portion of a firm's bottom line.