Last week, AM Best revised its outlook on #3 fronting carrier Trisura’s financial strength ratings to A- (as it affirmed them).

The move reflected the ratings agency’s view that improvements are needed in the listed Canadian fronting company’s operational risk management processes around captives within its US operations.

This came after Trisura delayed reporting its year-end financials, before disclosing a C$81.5mn ($59mn) impairment (~15% of Q3 shareholder equity) related to the write-down of reinsurance recoverables on a single unnamed program.

It seems clear that the impairment, and AM Best’s decision to go negative, are external proof of the degree of under-appreciated risk being run in various parts of the fronting market.

In September last year, I published a piece following Mitsui Sumitomo’s takeout of Transverse at a bewildering price, in which I called out the dangers latent within the fronting sector, following a period of ostensibly massive success over the last five years.

“If you squint hard, a fronting company might just look like the next great insurance fee business opportunity, with the fixed fee it charges to provide paper to MGAs seeking backing from reinsurance capacity.

But with eyes wide open, it becomes very clear that fronting firms are insurance companies in brokers’ clothes.

And indeed, it is worse than that. They are highly leveraged balance sheet businesses that present as capital-lite fee businesses…

And despite these businesses being highly leveraged balance sheet plays taking increasing amounts of risk, they are in some cases run by executives with backgrounds in distribution, with business production seemingly the core value-creating activity.”

Those issues are now manifesting, with Trisura a canary in the coal mine.

I further argued that there were two central risks.

First, the fronting carriers of today are increasingly “hybrid” writers taking both quota-share risk and substantial tail risk, rather than businesses passing risk straight through.

Second, I noted that fronting carriers run huge reinsurance recoverables relative to their surpluses, leaving them exposed to significant counterparty credit risk.

“This process highlights some of the areas that can be a risk in this model”

It is this second issue that tripped up Trisura. The carrier explains the write-down as a function of “a disagreement over obligations under a quota share reinsurance contract”.

The issue arose in a catastrophe-exposed program involving a captive vehicle connected to an MGA. It reflected “the lack of sufficient collateral to support the recoverable”, AM Best said. Trisura’s language on the call left investors to infer that it may take legal action.

The impairment of C$81.5mn is substantial for a business of Trisura’s size, and it resulted in a full-year ROE of 6%, with a negative ROE of 12.2% in the US. Trisura also gave adjusted numbers in which it backed out the charge, which would have given it a group ROE of 20% and a US ROE of 14.3%.

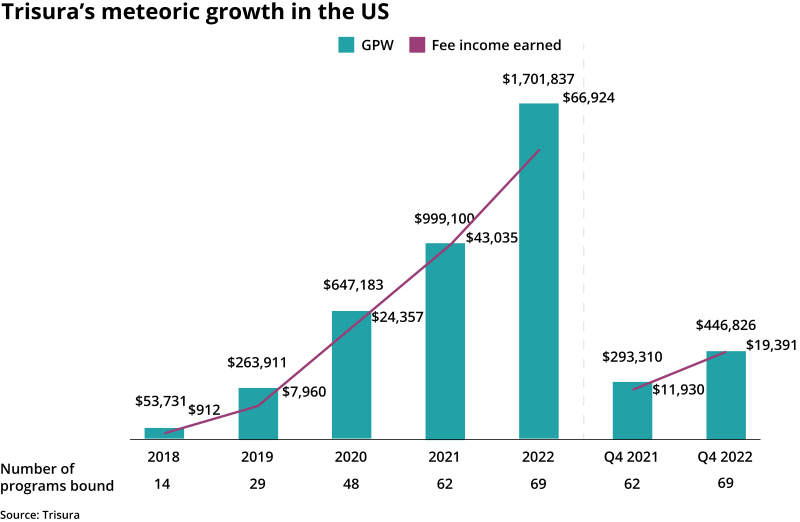

This is the result of reinsurance issues on one program. Trisura has 69 US programs in total.

The impact on Trisura’s stock has been painful, with the shares losing 29% of their value since the results were delayed in February.

Trisura is a poster child for the new age of fronting carriers. A market that was previously a State National monopoly has grown to over 25 players over the last eight years.

Founded in 2017, it has put up monster growth in the US to reach $1.7bn of GWP there, and $2.4bn across the group. Between the end of 2019 and year-end 2022, it added 40 programs in the US – more than one a month.

CEO David Clare said on the Q4 analyst call: “So it's very much a program in a situation that was unique that we don't think is present in other parts of the portfolio, but it's not one that we're shying away from.

“I think Trisura as an entity has grown a lot in the past five years. We've learned a lot as we've grown, as we've evolved our structure. And this experience is going to be one that certainly we benefit from in discussing and learning about the risk of the business.

“I don't want to say that in any way this risk process, this infrastructure changes dramatically as a result of this experience. We have a lot of established processes that we continue to invest in. But certainly, the learnings of this process highlights some of the areas that can be a risk in this model.”

His language is a little unclear on whether the monitoring and risk management was already strong, or if Trisura is now working to get it to standard. AM Best’s statement implies that it believes the latter.

Assurances from Trisura that this was a unique situation may prove correct, but it feels more like an assertion than a detailed case.

In its annual report, Trisura said it is confident in its remaining reinsurance recoverables, noting that 83% comes from rated reinsurers, with the remainder appropriately collateralized.

“An exhibit demonstrating this can be found in the notes to our financial statements.”

The exhibit seems to be a standard disclosure of reinsurance recoverables (reproduced below), which it published a version of before the impairment.

And of course, even with $173mn of A++ rated reinsurance, a counterparty’s ability to pay does not automatically translate to a willingness to pay.

Reinsurance disputes happen, and fronting carriers are highly exposed because they have so much leverage. Trisura’s GWP is levered 5:1 versus its equity, while its reinsurance recoverables are 4.4x its equity. Comparably sized specialty insurers typically run at below 1.5x – often far below.

With this kind of leverage, not much has to go wrong for things to go really wrong.

The negative outlook could also hit new business opportunities or weaken existing trading relationships, and Trisura’s competitors are sure to try to weaponize it in the coming months.

A cautionary tale

Trisura’s case stands as a warning of what happens when a fronting carrier fails to execute flawlessly on its reinsurance arrangements.

One of the foundation stones of State National’s success was its legendarily tight reinsurance contracts.

Sources suggest that the same degree of skill in managing counterparty credit risk is not in evidence across the sector, with fronting companies essentially competing by diluting standards.

This kind of competition is only likely to intensify as the new industry structure – featuring more than 25 players fiercely fighting for business – settles in, while the old structure becomes a distant memory.

Trisura’s problem also developed before significant market issues emerged. Ultimately the cycle will run out of steam, and growth will become more challenging for businesses used to growing 20%-60% a year, exacerbated by reduced flows to E&S where MGAs are overweight.

Trisura’s write-down is the first visible crack in the impressive edifice of the fronting space. It won’t be the last.