Over the past few months, there have been several disclosures impacting the livery insurance marketplace in New York City. The biggest issues have involved the American Transit Insurance Corporation (ATIC).

Last month, the company posted a $769mn loss in its regulatory filing for Q2 2024. ATIC is the largest of the companies that provide livery insurance in NYC, insuring an estimated 76,000 of the city’s roughly 114,000 for-hire vehicles in 2023.

While liquidation by the Department of Financial Services is the normal course of action for a loss of this scale, which the department has referred to as a “mandatory control level event”, the idea of leaving the majority of for-hire vehicles without insurance is an unsavory prospect for policy makers.

However, ATIC is not the only company in trouble. Hereford, the second-largest NYC livery insurer, also posted $141mn in losses for the quarter. Maya Assurance Company, another key part of the market, announced that it will be exiting the city’s livery market entirely. Citing the city’s no-fault insurance policies and “rampant fraud”, the insurer decided to cut its taxi insurance loose even though it made up half of Maya’s total book.

We have written about the problems faced by commercial auto insurers, Uber Insurance, and James River over recent years. Logically, we had to ask: could this livery issue snowball into a new crisis?

We came to the following conclusions:

One, there is something unique about NYC’s rideshare/livery market.

Two, a screening of the commercial auto space focusing on companies that were similar to ATIC (showing top-line growth coupled with a worsening surplus and worsening underwriting position) did not reveal “future ATICs”. Note that the livery and the rideshare market make up 5%-10% of the commercial auto space.

Three, we also reviewed broader commercial auto industry profitability and underwriting trends over the past few years.

We discuss these issues in detail below.

NYC’s livery market is uniquely problematic

New York is America’s largest city, and it’s also the only major city in the country where most households don’t own a car. While public transit handles most residents’ needs, for-hire vehicles help New Yorkers to get around when the subway isn’t an option.

While the yellow cabs of Manhattan (and the lesser known ”boro taxis” outside Manhattan) have historically filled this role, the rise of ridesharing companies such as Uber and Lyft in the 2010s has created major complications for the city’s livery insurance market. To the chagrin of the city’s taxi drivers – who paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for taxi medallions – Uber vehicles alone now outnumber yellow cabs by nearly eight to one.

This situation is not unique to NYC, as traditional taxis have dwindled steadily in number over the past decade as Uber and Lyft have grown in popularity. What is unique about New York’s situation is the requirement of all Uber and Lyft drivers to possess Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) licenses, and the insurance requirements of those licenses.

The chart below shows the difference between taxi insurance requirements and rideshare insurance requirements, on the basis of required limit per occurrence. Note that this information is sometimes inconsistent and that these figures were collected on a best-effort basis.

Unlike in most other major American cities, Uber and Lyft drivers in New York insurance limits match those of taxi cabs. Per New York’s insurance requirements for taxis, this means insurers must provide rideshare vehicles with insurance limits triple those seen everywhere else in the country.

New York is also a no-fault state, meaning that any insurance claims for personal injury in auto accidents up to a certain limit must be paid promptly by an insurance company regardless of fault or negligence on the part of involved parties. Note that 12 states in the US are no-fault states and historically fraud and abuse are correlated with impacting loss cost trends in these states.

For NYC’s TLC insurance, this means that any personal injuries sustained in any for-hire vehicles up to $200,000 must be paid out promptly by insurers without any lawsuit involved. Compounded by the high fraud that has been made particularly easy by this policy, NYC livery insurance is a source of constant, expensive and unmitigated claims.

The chart below shows the current estimated numbers of taxi and rideshare vehicles in each of the 10 largest cities in the US, as of 2023.

The rapid rise of Uber and Lyft has drastically increased the number of rideshare vehicles on the road in every major city, which is especially problematic in New York given the insurance requirements for TLC licensed drivers.

This massive influx of insured vehicles has created issues for the city’s livery insurers, forcing them to deal with far larger books than ever before.

In other words, many of the challenges seen in the NYC marketplace are also borne out of thinly capitalized, poorly managed carriers writing business in an inadequately priced marketplace.

The size of the marketplace in several other cities is much smaller in comparison, reducing the likelihood of bad actors capitalizing on the unmet demand for livery insurance.

Analysis of other minor commercial auto insurers did not reveal many companies like ATIC

With ATIC’s and Maya’s challenges, the logical question is: are other companies standing at a similar precipice?

Our analysis of several other players did not reveal any other company with an outsized market share like ATIC (which insured two-thirds of the livery market in NYC). Nonetheless, we looked at the entire commercial auto marketplace in the US which includes the rideshare and taxicab insurance marketplace.

Our exercise included the following filters: (1) Companies that were independent and not part of large national carriers, (2) unusually high premium growth for several years, (3) surplus declines for multiple years, and (4) persistent underwriting loss or close to it.

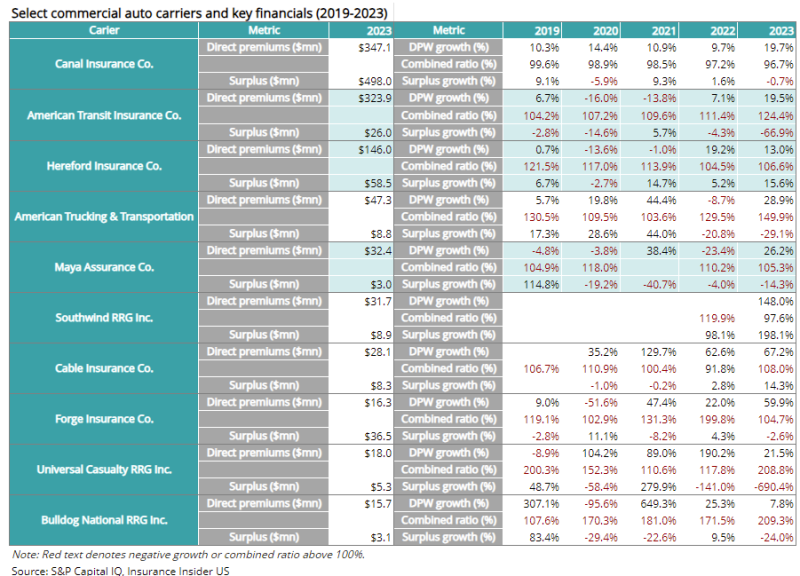

Based on that analysis, the list below shows carriers that met the criteria discussed above. We have highlighted ATIC, Maya, and Hereford. Note that the combined ratios for several other cohorts shown below are consistently above 100.

Note the larger premium sizes but the small capital base (surplus), which reflects solvency risk for ATIC, Maya and Hereford. However, the rest of the carriers that screened adversely had small books of business, so future challenges will not have a broader market impact.

Rideshare companies such as Uber and Lyft make up between 5% and 10% of the nationwide commercial auto market, with traditional taxi cabs making up far less than even that. The unique conditions of the New York market mentioned above are partially responsible for the poor results seen by Maya, Hereford and ATIC – though the latter also has its own aforementioned problems.

The list also includes several Risk Retention Groups (RRGs). An RRG is different from an insurance company since the primary purpose is self-insurance for similar types of risks. Unlike a traditional insurer, if an RRG fails, it does not have access to guaranty funds.

In terms of worse-than-anticipated losses, members of an RRG either have to pool additional resources or face unpaid claims and loss of coverage. Members of an RRG are aware of these risks when forming a self-insurance vehicle.

In short, companies in superficially similar circumstances to ATIC cannot be said to be experiencing the same issues, and those operating outside the NYC market seem unrelated entirely.

Commercial auto has been a problematic line for years

The commercial auto market, which includes trucks (short/long haul), delivery vans, pickup trucks, tractor-trailers, etc. has been severely impacted by persistent underwriting challenges for years.

Although the rideshare market is a small subset of the overall market, similar loss cost trends are applicable. These include large BI awards, medical expenses, litigation costs, labor and parts costs to name but a few.

The charts below compare the growth of commercial auto premiums with the industry combined ratio over the past decade.

In the past decade, the industry’s combined ratio for commercial auto insurance has been above 100% for every year except 2021, reaching as high of 111% in 2017. Recent issues such as the rising cost of vehicle repair and replacement have driven profitability down since the pandemic, but high turnover rates for truck drivers and nuclear verdicts related to those inexperienced drivers have plagued the industry for years.

Despite these challenges, the amount of premiums written in commercial auto has consistently risen over the period. Demand for commercial automotive insurance has only risen, and insurers will clearly still write business even in underperforming lines like this. Additionally, because of these profitability issues and the rising cost of auto repairs, state insurance departments have authorized rate changes that have increased the revenue stream generated by writing commercial auto insurance.

Other issues in commercial auto include low levels of capital surplus relative to premiums written, and a consistent need for reserve strengthening in recent accident years.

In other words, the loss cost trends in the livery market are a combination of broader loss cost trends intersecting with the city-level trends exacerbating the overall unprofitability of this marketplace.

In summary, the insolvency of some of the larger carriers in the NYC rideshare market does not increase the likelihood of similar problems cropping up in other major cities. Although unrelated troubles in the commercial auto market mean that we should not be surprised to hear of other carriers reporting issues, our analysis reveals that the situation in New York is unique and unrelated to the rest of the country. The problems with ATIC and the New York livery market is the result of thinly capitalized carriers operating in a particularly perilous market, rather than a new peril for the whole of commercial auto.