"You don't find out who's been swimming naked until the tide goes out," said Warren Buffet in response to a question on reinsurance market capacity in 1994.

What Buffett said in 1994 is still applicable 30 years on, and will likely be relevant to the reinsurance market in the near future.

With Hurricane Milton being less impactful vs initial projections, it might not end up being the litmus test for the industry that was anticipated, but the event should still drive better understanding of the exposure on Florida’s west coast and the insurance/reinsurance strategies pursued.

Historically, hurricanes impacting Florida follow a somewhat similar trajectory and form off the coast of Africa, strengthen over the Caribbean and then cross over on an east-to-west track.

That track often influences how insurance and reinsurance companies think of exposure, risk and capital management.

Very rarely have hurricanes crossed from the west to the east, which results in several new items to consider as the impact of Milton is understood over the next few weeks.

First, reinsurance markets will face a larger concentration of loss than with a typical hurricane, albeit higher retentions since Hurricane Ian will provide an indication of how this has cushioned their earnings loss. Our analysis shows that the smaller companies now pre-eminent in the state cede out meaningful premiums. We also looked at the top reinsurance partners using a statutory analysis. We would note that it's still early days, and the interplay of the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund (FHCF), retro writers and ILS funds remains to be fully carved out.

Second, exposure data might be an imperfect proxy for share of loss. We analyzed the probable maximum loss (PML) data for several publicly traded reinsurers/hybrids. We would note that although longer-term PMLs have trended down, they are up for Arch, Everest and PartnerRe since Ian. Nonetheless, historically, PMLs have been an imperfect proxy for actual losses.

Third, Milton's potential loss could be more of an earnings event than a capital event and aid in some degree of rate hardening at the upcoming renewals. We analyzed recent catastrophe losses as a percentage of equity, and prior losses had double-digit impacts for the Floridians and mid-to-single-high digits for the reinsurers/hybrids.

We discuss these points in detail below.

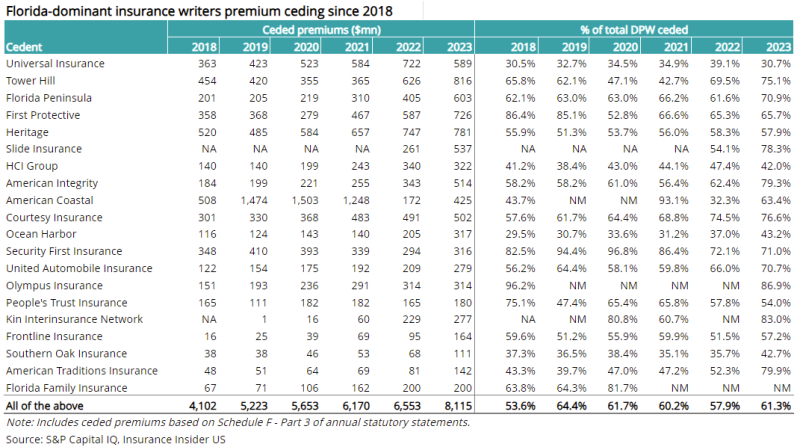

Florida insurers cede 60% of their premiums, which makes this a reinsurance-heavy event

The table below shows premiums ceded by the Florida dominant carriers over 2018-23. The cohort shown below cedes out 61.3% of its premiums as of year-end 2023. The numbers have continued to rise due to rate increases, and the Florida market is buying higher coverage levels from the FHCF.

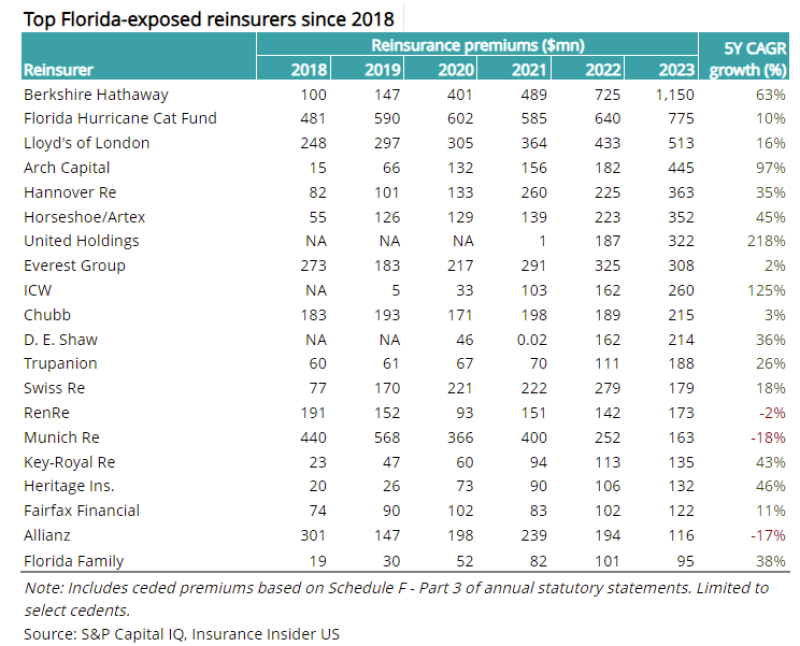

The next table looks at the largest reinsurance partners of business written in Florida.

Any state-level Schedule F analysis comes with several caveats. For one thing, the ceded premiums seen here come from all lines, including casualty and non-catastrophe property. There is also a lag effect, given that catastrophe treaties roll over with mid-year renewals, so a change in buyer or seller behavior would not be captured here. (It is known that Berkshire Hathaway dropped a major participation on the Florida Citizens reinsurance program this year, for example.)

Additionally, the analysis does not consider intercompany reinsurance and third-party reinsurance (retro) to limit any company’s losses. It does not capture all reinsurance facilities and ILS instruments, as well as fronting facilities.

Nevertheless, larger Bermuda reinsurers/hybrids continue to play an essential role in the marketplace.

As discussed above, Florida domestics will pay out any potential losses up to their retention, after which the FHCF will kick in. Once that is breached, the losses are ceded out to the reinsurance partners, depending on the program.

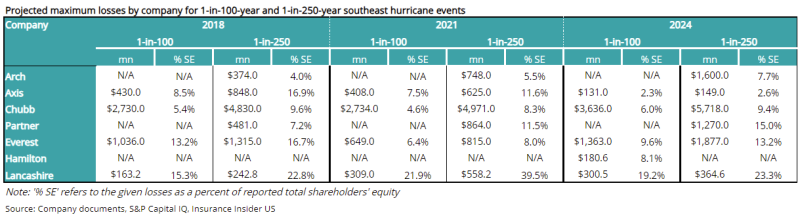

Exposure data is an imperfect proxy for this storm

Many reinsurance companies provide exposure data that shows the firm's potential loss at different interval levels for different regions.

This data is shown as PML for different return periods, and one can use this to calculate a hypothetical hit to equity.

The chart below shows this data for 2018 vs 2023. However, historically, there has been a disconnect between the share of losses and PML data.

This is true for a few reasons:

1. This information is based on historical data, and there is not enough data for a west-to-east hurricane track and its impact on losses.

2. This data does not give insight into geographic concentration, whether one reinsurer is reinsuring more on the west coast vs the other on the east coast.

3. Even though external and internal catastrophe models have continued to be refined over time, they remain sensitive to data input challenges and errors.

On the surface, it would seem that Arch, PartnerRe and Everest have grown that exposure, but we would caution against that conclusion without a deeper by-county dive. The same goes for the decline in PMLs.

Based on the latest information, it appears that Milton will not be a 1-in-100 return period event.

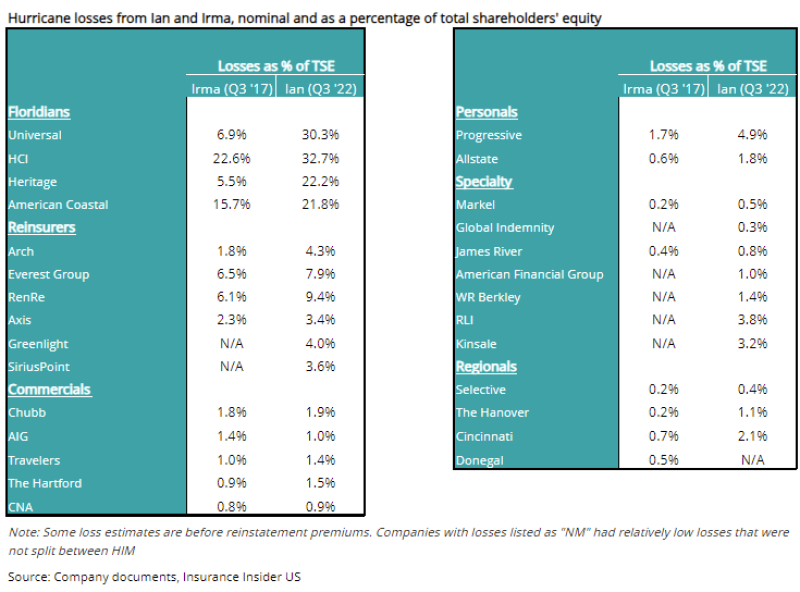

Catastrophe losses for Ian and Irma point to Milton being an earnings hit but not a game changer

Hurricane Irma was a $33bn hit to the (re)insurance industry in 2021 dollars, while Hurricane Ian was initially discussed as a $50bn loss. Based on preliminary estimates, it appears that this loss could be closer to Ian than Irma. This comes on top of Hurricane Helene, which could be a $10-$15bn loss.

The table below shows historical catastrophe losses as a percentage of equity. Both Ian and Irma equated to a mid-to-high single-digit loss for reinsurers and low-single digits for commercial insurers.

This is lower in comparison to the losses from the 2005 hurricane season, which was 10%-30% for the reinsurers and mid-to-high single digits for the commercial insurers.

In other words, when thinking about the PMLs and historic losses, Milton would be more of an earnings event for the (re)insurance space.

Taking a step back, this loss will potentially be enough to pressure reinsurance rates at the upcoming January 1 renewals, which include property, casualty and specialty lines, and reverse the prior anticipation of a decline of 5%-10%. Further impact will be felt at June 1, when regional Florida covers are renewed in most cases.

A similar scenario will likely prevail for commercial property insurance, which saw some declines to mid-single digits in the third quarter compared to high-single digits in the second quarter.

In summary, though the losses from Milton will be lower than anticipated, this event does have the potential for an uneven impact as Florida domestics have passed on significant risk to reinsurers. However, the impact on commercial insurers should be less significant due to the shift in Milton’s path as well as its wind speeds at landfall.